Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS) affects people of all ages, including children. Their diagnosis can be a big adjustment for the whole family. However, understanding your child’s diagnosis, care, and resources can help them to live a long and meaningful life.

In honour of National Child Day, celebrated each year in Canada on November 20, this article is dedicated to children with LDS.

How is LDS categorized?

Loeys-Dietz syndrome is categorized as rare, inherited, and complex. Understanding these categorizations can help us to understand challenges and potential solutions for LDS families.

Children and rare, inherited disease

A disease is classified as rare when it affects less than 1 of every 2,000 people. However, the rare disease category is quite common; in Canada, 1 in 12 people are affected by rare disease, and 2/3 of those are children.

An inherited disease is caused by a change in an individual’s genetic information and may be passed from parent to child. In pediatric hospitals, about 25% of occupied beds and 40% of costs are due to children with inherited diseases.

Diagnosing a rare disease can be difficult for medical professionals and families. Medical professionals may be unfamiliar with the disease and unable to make a clinical diagnosis, based on the signs and symptoms of a disease. For families, waiting for a diagnosis can be emotionally and financially challenging.

For conditions like LDS that are both rare and inherited, genetic testing may lead to a diagnosis. Accurate genetic diagnosis can improve medical care by providing more personalized prognosis, treatment, and monitoring for your child. Diagnosis can also allow your family to access disease-specific support, understand the condition and your choices, and pursue genetic testing for other family members. For more information about genes, genetic testing, and LDS, click here.

How do I explain an LDS diagnosis to my child?

Explaining an LDS diagnosis to your child is difficult. But, having this conversation will give your child the power to understand their body and feel more in control of their life. The following suggestions may be helpful for you and your family:

- Set aside time to talk when your child is free and you are able to focus on their needs.

- Give clear, honest, and age-appropriate information and answers to your child’s questions.

- After the initial conversation, check in with your child regularly. Ask about their feelings and guide them to express themselves through creative activities like play, art, and writing.

Reading about chronic illness may help your child and their siblings to identify with others and learn more about their own bodies and feelings.

- For picture books, click here

- For books for school-aged children (ages 5 to 10), click here, here, and here

- For books for older children (ages 8-10 and up), click here

- For books for teenagers, click here

Your child may find it comforting to connect with others who have LDS. The Loeys-Dietz Syndrome Foundation in the United States offers:

- For children ages 9-12, a monthly Kids Club

- For teenagers ages 13-18, a monthly Game Night and Teen Talk Night

For professional advice and support for you and your child, ask your genetic counsellor or doctor for a referral to a mental health professional.

Children and complex medical care

It can be difficult to manage complex medical issues and receive holistic care. Challenges can include a geographic barrier to access specialized pediatric care, a lack of communication between medical specialists and locations of care, and difficulty finding new doctors when children become adults. Substantial responsibility often falls on the family to learn medical information and coordinate care.

To improve care and facilitate access to care, we recommend several organizational strategies.

- Have a care plan, created by a physician with the family’s input, that outlines your child’s major medical needs.

- From their medical needs, create a care map of all your child’s providers and organizations.

- Establish a key worker, a health professional who can be the main point of contact between your family and medical providers, provide resources to your family, and coordinate providers.

- Providers should work together as multidisciplinary teams from multiple specialties and locations of care. Although the exact specialists needed will depend on your child’s medical needs, it is generally recommended to have a geneticist, cardiologist, orthopedist, ophthalmologist, rehabilitation medicine specialist, and mental health professional. Learn more about multidisciplinary LDS clinics here.

Children and LDS

Signs and symptoms

Children with LDS may experience many of the same symptoms as adults. To learn more about the signs and symptoms of LDS, check out our Head to Toe. This document will continue to grow and evolve as more people are diagnosed, more research is completed, and we learn more about LDS.

Treatment and monitoring

Depending on your child and their needs, their doctors will develop a plan to treat and monitor their medical conditions. Monitoring may include measuring arteries and reporting methods for these measurements can differ between children and adults.

Why do we measure arteries?

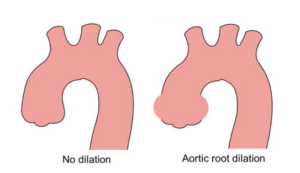

Your child’s doctor may measure their arteries to see if they are growing in size. LDS may cause arteries to dilate (grow larger in diameter) and dissect (grow large enough to tear layers of the artery). The most common area for dissection is the aortic root. The aortic root is connected to the heart and is part of the aorta, the artery through which blood from the heart travels to the rest of the body. Aortic root size is measured as the maximum dimension at the sinuses of Valsalva.

Your child’s doctor can use aortic root size and factors like family history, aortic function, and growth rate to decide if preventative surgery is recommended. Surgical is generally recommended for adults and adolescents once the maximum dimension reaches 4.0 cm. For children, surgery is usually recommended once the aortic root exceeds 1.8-2.0 cm and the 99th percentile, or once the Z-score is greater than 3.5.

Why are measurements reported as size, percentile and Z-score?

Aortic root size can be reported as an absolute size, percentile or Z-score.

For adults, aortic root size is usually described as an absolute size in mm or cm and compared to a “normal range” of sizes. For children, aortic root size can be reported as an absolute size, but this method can be difficult to use because the “normal range” of sizes is always changing as children grow and age. To account for their growth, physicians often use percentiles and Z-scores.

In medicine, a percentile compares one person’s physical measurement to a range of measurements from other people of the same age, sex, body size, etc. The range of measurements is split into 100 groups, each group is called a percentile, and the groups range from the 1st to 99th percentile. The greater your child’s percentile, the greater their measurement is compared to others.

In medicine, a Z-score compares a person’s physical measurement to the average measurement for their age or body size. The greater your child’s Z-score, the further it is from the average.

Are you a caregiver?

When caring for someone with LDS, it is important to take care of yourself. Canadian caregivers report facing mental health issues, stress, isolation, and financial burden. To lighten the load, consider reaching out to family, friends, support groups like Loeys-Dietz Families, financial assistance programs, counsellors, social workers, and other professionals.

For financial assistance programs:

- For medical travel expenses in Quebec, visit the Government of Quebec and Fondation en Coeur

- For benefits and support programs in Canada, visit the Government of Canada Benefits Finder and Heart and Stroke Foundation

As a caregiver or parent, you are in the best position to know your child and advocate for them. If you feel that something is medically or otherwise “off” with your child, trust your gut and seek help.

For information:

For more information about genes, genetic testing, and LDS, click here.

For signs and symptoms of LDS, check out our diagnostic Head to Toe

For support for kids:

For books on chronic illness:

- For picture books, click here

- For school-aged children (ages 5 to 10), click here, here, and here

- For older children (ages 8-10 and up), click here

- For teenagers, click here

For peer support, the Loeys-Dietz Syndrome Foundation in the United States hosts:

- For children ages 9-12, a monthly Kids Club

- For teenagers ages 13-18, a monthly Game Night and Teen Talk Night

For support for adults:

For peer support, visit a community-run, closed Facebook group: Loeys-Dietz Families

For a Parent Toolkit on diagnosis, school, and more, visit the Marfan Foundation here

For our Support Centre, click here

For multidisciplinary LDS clinics, click here

For financial assistance programs,

- For medical travel expenses in Quebec, visit the Government of Quebec and Fondation en Coeur

- For benefits and support programs in Canada, visit the Government of Canada Benefits Finder and Heart and Stroke Foundation

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Rare diseases: More common than you think. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51888.html

Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders. About CORD. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.raredisorders.ca/about-cord/

Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders. Canada’s rare disease caregivers under immense stress, struggling with mental health issues, isolation and financial burden. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: http://www.raredisorders.ca/content/uploads/CORD_NationalFamilyCaregiverDay_PressRelease_04022019_FINAL1.pdf

Curtis AE et al. 2016. The Mystery of the Z-Score. Aorta (Stamford). 4(4): 124-130. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5217729/

Dewan T, Cohen E. 2013. Children with medical complexity in Canada. Paediatric Child Health. 18(10): 518-522. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3907346/

KidsHealth. Caring for a Seriously Ill Child. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/seriously-ill.html

Loeys BL, Dietz HC. 2008 [updated 2018 Mar 1]. Loeys-Dietz Syndrome. GeneReviews. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1133/

Longdom Publishing. Inherited Diseases. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.longdom.org/scholarly/inherited-diseases-journals-articles-ppts-list-385.html

Manchola-Linero A et al. 2018. Marfan Syndrome and Loeys-Dietz Syndrome in Children : A Multidisciplinary Team Experience. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia. 71(7): 585-587. https://www.revespcardiol.org/en-marfan-syndrome-loeys-dietz-syndrome-in-articulo-S1885585717302773

The Marfan Foundation. Aortic Root Z-Scores for Children. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://marfan.org/dx/zscore-children/

Mayo Clinic. Aortic dissection. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/aortic-dissection/symptoms-causes/syc-20369496

National Organization for Rare Disorders. Barriers to Disease Diagnosis, Care and Treatment in the US: A 30-Year Comparative Analysis. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NRD-2088-Barriers-30-Yr-Survey-Report_FNL-2.pdf

Office of the Child and Youth Advocate Alberta. National Child Day. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.nationalchildday.ca/

Saliba E, Sia Y. 2015. The ascending aorta aneurysm: When to intervene? International Journal of Cardiology. Heart & Vasculature. 6:91-100. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5497177/

Sophocleous F et al. 2019. Determinants of aortic growth rate in patients with bicuspid aortic valve by cardiovascular magnetic resonance; Figure 1. Open Heart. 6: e001095. https://openheart.bmj.com/content/6/2/e001095

- Links to license: here and here

- Changes made: Figure 1 cropped to include only images relevant to this text.

The Washington Post. How to talk to your child about serious illness. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2017/03/03/how-to-talk-to-your-child-about-your-serious-illness/

Wright CF, FitzPatrick DR, Firth HV. 2018. Paediatric genomics: diagnosing rare disease in children. Nature Reviews Genetics. 19: 253-268. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg.2017.116